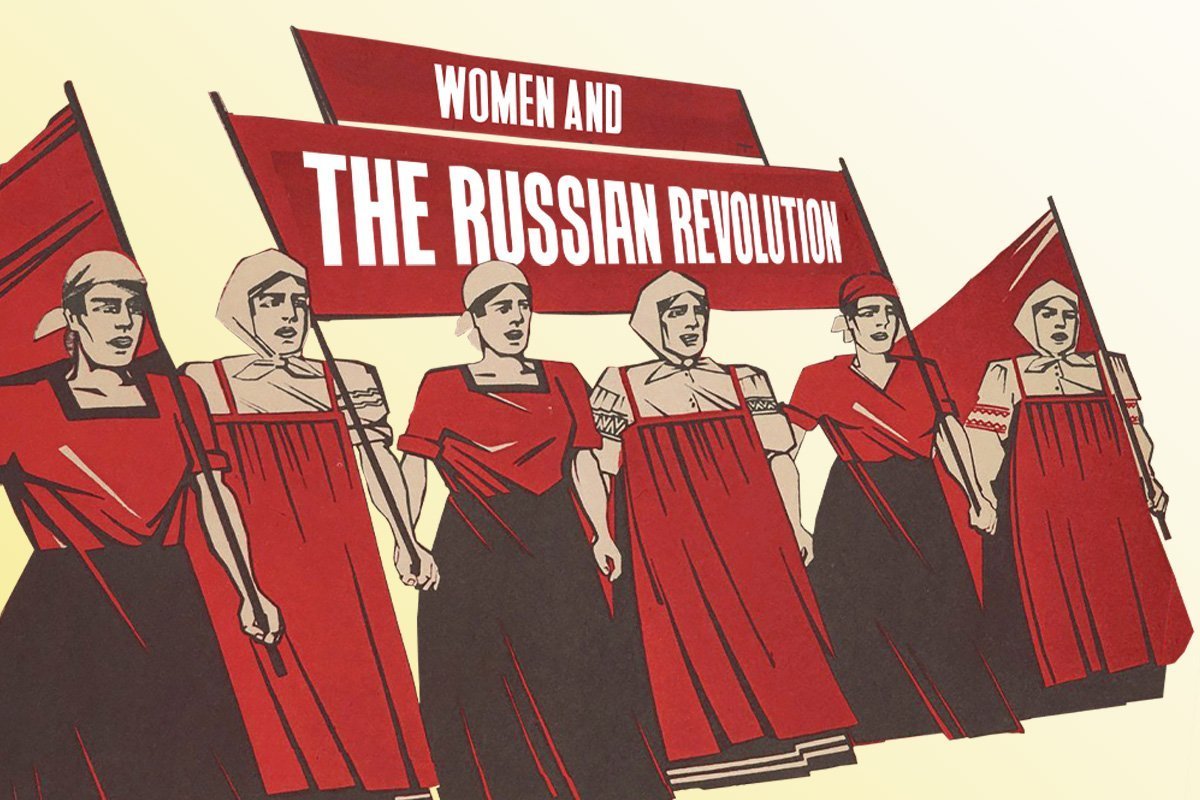

In the Russian Revolution, workers successfully took power and began to transform society for the first time in history. By taking control of the economy, they opened up the possibility of changing social relations and everyday life.

One of the major areas of society they tried to change was the lives and conditions of women, and the structure of the family.

Today, even in the most developed countries in the world, women have worse rights than in revolutionary Russia 100 years ago.

How were the Bolsheviks able to make such profound changes to women’s conditions so long ago? And how can we achieve something like that today?

Mothers and wives

Tsarist Russia was an absolutist and deeply reactionary regime. It was closely linked to the Orthodox Church, which maintained a crushing material and ideological control of the population.

The church was a tool of the state to keep people down. It owned vast tracts of land, and had an annual income of over 150 million rubles. It preached – as it still does today – that a woman has no role other than as a mother and a wife.

Women were the property of men, and this was codified in Tsarist law. Men even had the right to beat their wives.

A law from before the revolution advised that:

“If a wife refuses to obey and pays no attention to what her husband tells her, it is advisable to beat her with a whip according to the measure of her guilt. But if her fault is very serious, then strip her off and give her a sound beating.”

In fact, domestic violence was once again decriminalised in Russia in 2017, highlighting the regression society has undergone with the return of capitalism.

The control of women went well beyond violence, as evidenced by this law:

“A woman must consult her husband at all times. If she receives an invitation, only her husband can permit it. But she must talk with her guests of nothing but embroidery and household matters.”

There was a material basis for this oppression in the backwardness of the economy. Russian capitalism didn’t start developing until the 1880s. Although capitalism had begun to shake Russian society out of feudal conditions and ideas, this occurred more slowly and later than elsewhere.

In the early-20th century, only about 4-5 million out of 150 million people were workers. The rest were largely peasants. This is crucial, because it was only in the urban working class that the struggle for the emancipation of women began.

According to an 1897 report, only 13% of women were literate. Girls received one year of elementary education, and then worked in the fields and did domestic chores for the household. The effect of this was to isolate women and girls from one another, and to prevent them from organising and discussing.

As we celebrate International Working Women’s Day, we are excited to announce the publication of a new book, ‘Women, Family and the Russian Revolution’ by John Peter Roberts and Fred Weston.

💥 Find out more and pre-order your copy now at https://t.co/2zvt52d5Fv 💥 pic.twitter.com/ob0QB5jgoO

— Wellred Books (@WellredBooks) March 8, 2023

Where there were female proletarians, they were paid much less than men. They were not allowed to join trade unions, as they were thought to be less intelligent, and therefore likely to hold the movement back.

Women in Russia had far worse conditions than in the rest of Europe. For comparison, in Britain, 40% of women were literate by 1800, and 77% were by 1855. Life expectancy for British women in 1900 was 50, whereas in Russia it was 30.

This backwardness makes the gains made for women in the Russian Revolution all the more impressive.

Increasing organisation

With the development of capitalism in Russia towards the end of the 19th century, workers had been brought together in increasingly large workplaces. Women were brought into these workplaces, and therefore removed from their isolation in the home.

With the development of capitalism in Russia towards the end of the 19th century, workers had been brought together in increasingly large workplaces. Women were brought into these workplaces, and therefore removed from their isolation in the home.

This was an enormously progressive development, and had significant implications. As Lenin explained:

“By destroying the patriarchal isolation of these categories of the population, who formerly never emerged from the narrow circle of domestic relationships, by drawing them into direct participation in social production, large scale machine industry stimulates their development, and increases their independence, in other words creates conditions of life that are incomparably superior to the patriarchal immobility of pre-capitalist relations.”

(Lenin, The development of capitalism in Russia, 1889)

Consequently, from the 1890s we do see some steps taken forward for women. They participated in some strikes. And some education was given to them by the government in order that they could be more productive workers.

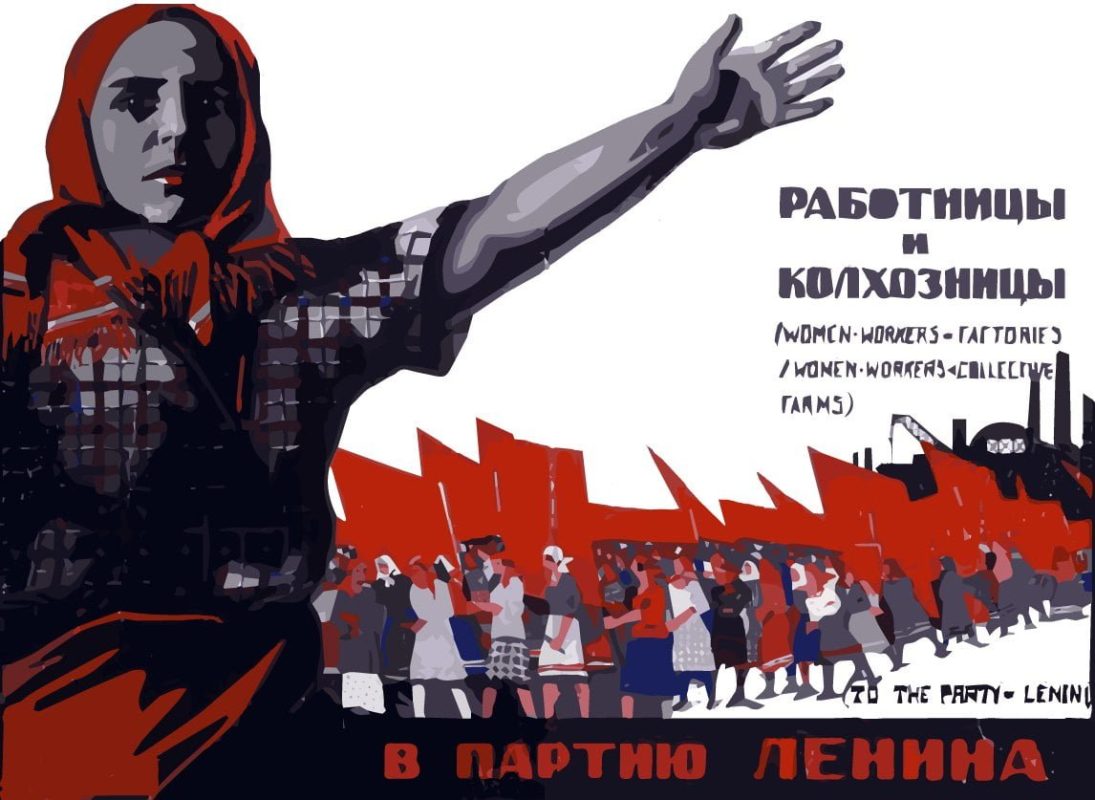

16.5% of the delegates elected to the first Soviet in the 1905 revolution were women – a sign of the increased organisation of women. WWI greatly accelerated this, due to the increasing entry of women to the workforce. By the end of the war, they accounted for 40% of the workforce in large-scale industry. In Moscow, 60% of all textile workers were women.

The Bolsheviks recognised the significance of this. They produced a journal for working women, Rabotnitsa. In its production, female representatives from many factories discussed its articles with the editorial board.

Rabotnitsa didn’t only write about women’s issues. And it didn’t separate the struggle of female and male workers. It wrote about the struggle for socialism as a whole. It explained that real equality can only be achieved with the socialist transformation of society.

Revolution

As such, the struggle of working-class women turned out to be a significant factor in the development of the Russian Revolution in 1917.

As soon as the Bolsheviks came to power, they passed a series of laws ensuring legal equality for men and women.

Women were no longer to be men’s property, and were free to divorce without recourse to their husband or the church.

Significantly for that time, women were granted the right to vote. In 1917, the only other countries in Europe in which women could vote were Denmark and Norway.

The Bolsheviks granted free access to abortion in 1920 – the first country in the world to do so. They established special maternity wards and paid maternity leave before and after birth – something not granted in Britain until 1975.

By 1926, marriage didn’t have to be registered, divorce was made as easy as possible, and the concept of illegitimate children was abolished.

The Bolsheviks decreed the eight-hour working day four days after coming to power, making it easier for working women to have the time to participate in politics. They also established public laundries and canteens to free women up from domestic chores.

Socialisation

Why was the revolution able to make such huge changes?

Why was the revolution able to make such huge changes?

Because the revolution seized hold of the means of production, the economic base of society, conditions for women could begin to be changed.

The origins of women’s oppression lie in the existence of private property. By abolishing that, the Bolshevik Revolution made it possible to end this oppression.

Nationalising the economy brought wealth into society’s hands. This gave the potential for domestic, private labour to be done socially and collectively.

This could significantly free-up women’s time, and thus remove many of the key barriers in the way of them participating in wider society – in the workplace, politics, culture, etc.

Instead of being forced to stay at home to care for children and the elderly, women could go to work alongside men. And instead of returning from work and then making dinner and washing clothes, just as most women do today, they could read, discuss, and organise.

The 1919 programme of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union made socialisation of domestic labour its conscious aim:

“Not satisfied with the formal equality of women, the party strives to free women from the material burden of obsolete domestic economy, by replacing it with house communes, public dining halls, central laundries, creches etc.”

This was a central, not secondary demand. But none of this was possible unless the means of production were nationalised and placed under the democratic control of workers – the key difference between a capitalist and socialist economy.

Role of women in struggle

The planned economy began to bring women out of the home to be independent, class conscious workers, in a way that had never been achieved anywhere else.

The planned economy began to bring women out of the home to be independent, class conscious workers, in a way that had never been achieved anywhere else.

What active role did women play in this process? It is well known that women workers kick-started the February Revolution in 1917. But there is much more than that.

Women were elected to soviets and played leading roles in them. Alexandra Kollontai was the People’s Commissar for Welfare in the first Soviet government, making her the first female minister in the world.

Women were organised in the Red Army to defend the revolution. They carried out all manner of daily tasks in the reconstruction of society.

Women were organised – but not along ‘feminist’ lines, i.e. only regarding ‘womens’ issues. They were engaged also as workers who needed to be involved in this revolution as much as anyone else. They were revolutionaries organising the revolutionary transformation of society.

In 1919, the Communist Party created a women’s department of its Central Committee, led by Kollontai and Inessa Armand. Its purpose was to organise women in the factories and to educate them politically. It had 2.8 million women organised in socialist reading groups.

They proposed and fought for improvements – such as the introduction of legal abortion in hospitals.

Having a revolution does not automatically liberate everyone, even if it provides the material and political basis for doing so. This body therefore helped develop the legislation, policies, and organisation needed to carry out this transformation.

Limits

The planned economy provided the basis for all this. But it was not by itself sufficient, as Lenin and Trotsky understood. The USSR lacked the material resources and productivity to realise their plans. Socialised childcare and laundries were never fully achieved for lack of resources.

Trotsky remarked that “a deep going plough is needed to turn up heavy clods of soil”. In other words, the conscious engagement of the working class is necessary to rid society of the prejudices of millenia, including sexism.

A workers’ state demands the greatest participation of the working class, and the education necessary for this. Education was required to break these prejudices, inherited from the previous period.

For instance, the 1921 congress of the Communist International stated that its aim was: “To fight the prejudices against women held by the mass of the male proletariat, and to increase the awareness of working men and women that they have common interests.”

They also aimed to: “Conduct a well planned struggle against the power of tradition, against bourgeois customs and religious ideas, clearing the way for healthier and more harmonious relations between the sexes, guaranteeing the physical and moral vitality of working people.”

This work was vital, but limited by the economic conditions of Russia at the time. The revolution inherited an extremely backward economy.

Then, in 1918, a counter-revolutionary civil war was launched by the bourgeoisie in alliance with the imperialists. The economy was heavily damaged by this. And time and resources that could have been devoted to the emancipation of women, were instead dedicated to fighting this war.

The means of production were far from able to provide enough for everyone, let alone to shorten the working week and provide childcare for all etc. The Bolsheviks had the correct idea with their plans for education against prejudices, but the conditions that gave rise to these prejudices could not be overcome.

Counter-revolution

On the basis of this backwardness, the Stalinist bureaucracy arose and usurped power from the working class in a political counter-revolution. This found an expression in the status of women.

Stalin based himself on conservative social forces and ideas. As a result, he encouraged some of the worst prejudices on the role of women.

Abortion was illegalised, and prizes were established for women who had many children. Divorce was made more expensive and harder to obtain. Childcare hours were cut. Girls and boys were educated separately, with girls taught about being good housewives.

Unsurprisingly, this counter-revolution meant that many people reverted to their old ideas. Nevertheless, even with these reversals, the USSR made huge advancements for women thanks to the planned economy.

Women still received full maternity pay, for 56 days either side of birth. Compare this to the USA today, where there remains no obligation for paid maternity leave at all.

The first five-year plan (1927-32) led to the number of nurseries rising from 2,000 to 20,000. There were 12 million spaces for children in nurseries.

The cost of a nursery place was about one tenth of an average workers’ wage. Contrast this to today, where in Britain one-in-five parents with children under five spend between a fifth and a third of their salary on childcare, with 15% spending over half.

Rights vs material conditions

Why is it that today we still don’t have these rights and social gains?

Only the seizure of power by the working class can deliver real material equality for women, as it is not in the interests of the capitalist class to do so.

Capitalism benefits from domestic tasks being carried out in the home, privately. Public spending on these domestic tasks is not in the interests of capitalists, as it would eat into their profits.

This results in pressure on women to remain in the home, for lack of an affordable alternative. Capitalists also propagate ideas to justify this – such as the idea that women have a better ‘natural nurturing role’ as mothers.

Capitalism can pass laws enshrining equality, but it cannot deliver this. For example, only 1% of rape accusations end in conviction.

In Britain, there is legal equality for men and women, and laws prohibiting sexual violence. And yet there is a 20% gender pay gap; women do 13 hours of domestic labour per week, compared to 6.5 hours for men; 77% of domestic abuse victims are female; and one-in-four women will be raped or sexually assaulted in their lifetime.

Today, even reforms won in the past are being clawed back thanks to the crisis of capitalism. Austerity is worsening women’s lives and pushing them into the home.

This will continue, despite all the campaigns we have about the ills of sexist attitudes. No amount of calls for equal representation under capitalism will stop this, because the material conditions of capitalism in crisis do not allow it.

Struggle for socialism

To emancipate women today, we mustn’t be swayed by bourgeois methods such as ‘all women shortlists’, or by laws to increase the number of women in boardrooms, etc. None of these things will achieve anything, as the statistics on the gender pay gap today show.

To emancipate women today, we mustn’t be swayed by bourgeois methods such as ‘all women shortlists’, or by laws to increase the number of women in boardrooms, etc. None of these things will achieve anything, as the statistics on the gender pay gap today show.

The truth is that for women to truly and fully participate in political life, they have to be freed from domestic chores to the same extent as men. All domestic habits and responsibilities must be completely revolutionised, and made social instead of private.

This requires a global revolution, to take power out of the hands of the capitalists. To be successful, this requires the maximum unity and active participation of all of the working class – men and women. In the process of common struggle, many of the prejudices from the past will be overcome.

The USSR was able to begin to put such laws into practice by making the necessary resources available thanks to the planned economy. This provided the potential to harmonise all of society’s production in a rational way, to meet the needs of society as a whole, instead of for the profit of a few billionaires.

Imagine what could be achieved with a planned economy with the technology and wealth of modern society worldwide.

Already we have an economy in which everything is produced socially. But capitalists privately appropriate that wealth. We have the means to provide socialised domestic work. In fact, we could automate a large amount of menial work, freeing everyone from this drudgery. The technology is largely there now. But under capitalism, such investments for the good of society will not take place.

By freeing people from such work, solving the housing crisis, and making women economically independent, we could also end unhealthy relationships that persist because of economic necessity. Equally, many relationships that break down under capitalism due to financial stress would not do so under socialism.

Relationships could then develop on the basis of a genuine, mutual bond. This, alongside the provision of high-quality, free care for children and the elderly, would transform the shape and structure of the family. This is what is needed to emancipate women and the whole of humanity.

Yes, we fight for reforms now, under capitalism. But we know that whilst capitalism may grant these on paper, it will remain incapable of actually liberating women.

To solve the problems of women’s oppression, we must fight to fundamentally change society. And that means fighting for revolution.